Via Zach Holman’s blog post I found an interesting Twitter discussion that kicked off with these questions:

A couple of tough questions for all of you:

1. Is the date2022-06-01equal to the time2022-06-01 12:00:00?

2. Is the date2022-06-01between the time2022-06-01 12:00:00and the time2022-12-31 12:00:00?

3. Is the time2022-06-01 12:00:00after the date2022-06-01?

I’ve been involved for two years and counting1 in the design of Temporal, an enhancement for the JavaScript language that adds modern facilities for handling dates and times. One of the principles of Temporal that was established long before I got involved, is that we should use different objects to represent different concepts. For example, if you want to represent a calendar date that’s not associated with any specific time of day, you use a class that doesn’t require you to make up a bogus time of day.2 Each class has a definition for equality, comparison, and other operations that are appropriate to the concept it represents, and you get to specify which one is appropriate for your use case by your choice of which one you use. In other, more jargony, words, Temporal offers different data types with different semantics.3

For me these questions all boil down to, when we consider a textual representation like 2022-06-01, what concept does it represent? I would say that each of these strings can represent more than one concept, and to get a good answer, you need to specify which concept you are talking about.

So, my answers to the three questions are “it depends”, “no but maybe yes”, and “it depends.” I’ll walk through why I think this, and how I would solve it with Temporal, for each question.

You can follow along or try out your own answers by going the Temporal documentation page, and opening your browser console. That will give you an environment where you can try these examples and experiment for yourself.

Question 1

Is the date

2022-06-01equal to the time2022-06-01 12:00:00?

As I mentioned above, Temporal has different data types with different semantics. In the case of this question, what the question refers to as a “time” we call a “date-time” in Temporal4, and the “date” is still a date. The specific types we’d use are PlainDateTime and PlainDate, respectively. PlainDate is a calendar date that doesn’t have a time associated with it: a single square on a wall calendar. PlainDateTime is a calendar date with a wall-clock time. In both cases, “plain” refers to not having a time zone attached, so we know we’re not dealing with any 23-hour or 25-hour or even more unusual day lengths.

The reason I say that the answer depends, is that you simply can’t say whether a date is equal to a date-time. They are two different concepts, so the answer is not well-defined. If you want to do that, you have to convert one to the other so that you either compare two dates, or two date-times, each with their accompanying definition of equality.

You do this in Temporal by choosing the type of object to create, PlainDate or PlainDateTime, and the resulting object’s equals() method will do the right thing:

> Temporal.PlainDate.from('2022-06-01').equals('2022-06-01 12:00:00')

true

> Temporal.PlainDateTime.from('2022-06-01').equals('2022-06-01 12:00:00')

false

I think either of PlainDate or PlainDateTime semantics could be valid based on your application, so it seems important that both are within reach of the programmer. I will say that I don’t expect PlainDateTime will get used very often in practice.5 But I can think of a use case for either one of these:

- If you have a list of

PlainDateTimeevents to present to a user, and you want to filter them by date. Let’s say we have data from a pedometer, where we care about what local time it was in the user’s time zone when they got their exercise, and the user has asked to see all the exercise they got yesterday. In this case I’d use date semantics: convert thePlainDateTimedata toPlainDatedata. - On the other hand, if the

2022-06-01input comes from a date picker widget where the user could have input a time but didn’t, then we might decide that it makes sense to default the time of day to midnight, and therefore use date-time semantics.

Question 2

Is the date

2022-06-01between the time2022-06-01 12:00:00and the time2022-12-31 12:00:00?

I think the answer to this one is more unambiguously a no. If we use date-time semantics (in Temporal, PlainDateTime.compare()) the date implicitly converts to midnight on that day, so it comes before both of the date-times. If we use date semantics (PlainDate.compare()), 2022-06-01 and 2022-06-01 12:00:00 are equal as we determined in Question 1, so I wouldn’t say it’s “between” the two date-times.

> Temporal.PlainDateTime.compare('2022-06-01', '2022-06-01 12:00:00')

-1

> Temporal.PlainDateTime.compare('2022-06-01', '2022-12-31 12:00:00')

-1

> Temporal.PlainDate.compare('2022-06-01', '2022-06-01 12:00:00')

0

> Temporal.PlainDate.compare('2022-06-01', '2022-12-31 12:00:00')

-1

(Why these numbers?6 The compare methods return −1, 0, or 1, according to the convention used by Array.prototype.sort, so that you can do things like arr.sort(Temporal.PlainDate.compare). 0 means the arguments are equal and −1 means the first comes before the second.)

But maybe the answer still depends a little bit on what your definition of “between” is. If it means the date-times form a closed interval instead of an open interval, and we are using date semantics, then the answer is yes.7

Question 3

Is the time

2022-06-01 12:00:00after the date2022-06-01?

After thinking about the previous two questions, this should be clear. If we’re using date semantics, the two are equal, so no. If we’re using date-time semantics, and we choose to convert a date to a date-time by assuming midnight as the time, then yes.

Other people’s answers

I saw a lot of answers saying that you need more context to be able to compare the two, so I estimate that the way Temporal requires that you give that context, instead of assuming one or the other, does fit with the way that many people think. However, that wasn’t the only kind of reply I saw. (Otherwise the discussion wouldn’t have been that interesting!) I’ll discuss some of the other common replies that I saw in the Twitter thread.

“Yes, no, no: truncate to just the dates and compare those, since that’s the data you have in common.” People who said this seem like they might naturally gravitate towards date semantics. I’d estimate that date semantics are probably correct for more use cases. But maybe not your use case!

“No, no, yes: a date with no time means midnight is implicit.” People who said this seem like they might naturally gravitate towards date-time semantics. It makes sense to me that programmers think this way; if you’re missing a piece of data, just fill in 0 and keep going. I’d estimate that this isn’t how a lot of nontechnical users think of dates, though.

In this whole post I’ve assumed we assume the time is midnight when we convert a date to a date-time, but in the messy world of dates and times, it can make sense to assume other times than midnight, as well. This comes up especially if time zones are involved. For example, you might assume noon, or start-of-day, instead. Start-of-day is often, but not always midnight:

Temporal.PlainDateTime.from('2018-11-04T12:00')

.toZonedDateTime('America/Sao_Paulo')

.startOfDay()

.toPlainTime() // -> 01:00

“These need to have time zones attached for the question to make sense.” If this is your first reaction when you see a question like this, great! If you write JavaScript code, you probably make fewer bugs just by being aware that JavaScript’s Date object makes it really easy to confuse time zones.

I estimate that Temporal’s ZonedDateTime type is going to fit more use cases in practice than either PlainDate or PlainDateTime. In that sense, if you find yourself with this data and these questions in your code, it makes perfect sense to ask yourself whether you should be using a time-zone-aware type instead. But, I think I’ve given some evidence above that sometimes the answer to that is no: for example, the pedometer data that I mentioned above.

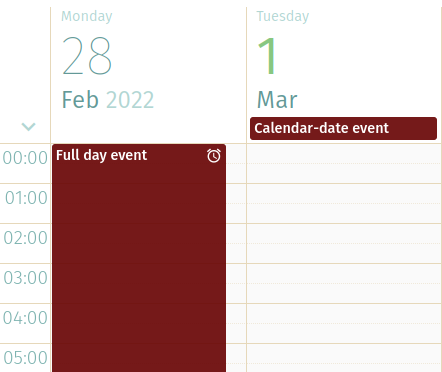

“Dates without times are 24-hour intervals.” Also mentioned as “all-day events”. I can sort of see where this comes from, but I’m not sure I agree with it. In the world where JavaScript Date is the only tool you have, it probably makes sense to think of a date as an interval. But I’d estimate that a lot of non-programmers don’t think of dates this way: instead, it’s a square on your calendar!

It’s also worth noting that in some calendar software, you can create an all-day event that lasts from 00:00 until 00:00 the following day, and you can also create an event for just the calendar date, and these are separate things.

“Doesn’t matter, just pick one convention and stick with it.” I hope after reading this post you’re convinced that it does matter, depending on your use case.

“Ugh!” That’s how I feel too and why I wrote a whole blog post about it!

How do I feel about the choices we made in Temporal?

I’m happy with how Temporal encourages the programmer to handle these cases. When I went to try out the comparisons that were suggested in the original tweet, I found it was natural to pick either PlainDate or PlainDateTime to represent the data.

One thing that Temporal could have done instead (and in fact, we went back and forth on this a few times before the proposal reached its currently frozen stage in the JS standardization process) would be to make the choice of data type, and therefore of comparison semantics, more explicit.

For example, one might make a case that it’s potentially confusing that the 12:00:00 part of the string in Temporal.PlainDate.from('2022-06-01').equals('2022-06-01 12:00:00') is ignored when the string is converted to a PlainDate. We could have chosen, for example, to throw if the argument to PlainDate.prototype.equals() was a string with a time in it, or if it was a PlainDateTime. That would make the code for answering question 1 look like this:

> Temporal.PlainDate.from('2022-06-01').equals(

... Temporal.PlainDateTime.from('2022-06-01 12:00:00')

... .toPlainDate())

true

This approach seems like it’s better at forcing the programmer to make a choice consciously by throwing exceptions when there is any doubt, but at the cost of writing such long-winded code that I find it difficult to follow. In the end, I prefer the more balanced approach we took.

Conclusion

This was a really interesting problem to dig into. I always find it good to be reminded that no matter what I think is correct about date-time handling, someone else is going to have a different opinion, and they won’t necessarily be wrong.

I said in the beginning of the post: “to get a good answer, you need to specify which concept you are talking about.” Something we’ve tried hard to achieve in Temporal is to make it easy and natural, but not too obtrusive, to specify this. When I went to answer the questions using Temporal code, I found it pretty straightforward, and I think that validates some of the design choices we made in Temporal.

I’d like to acknowledge my employer Igalia for letting me spend work time writing this post, as well as Bloomberg for sponsoring Igalia’s work on Temporal. Many thanks to my colleagues Tim Chevalier, Jesse Alama, and Sarah Groff Hennigh-Palermo for giving feedback on a draft of this post.

[1] 777 days at the time of writing, according to Temporal.PlainDate.from('2020-01-13').until(Temporal.Now.plainDateISO()) ↩

[2] A common source of bugs with JavaScript’s legacy Date when the made-up time of day doesn’t exist due to DST ↩

[3] “Semantics” is, unfortunately, a word I’m going to use a lot in this post ↩

[4] “Time” in Temporal refers to a time on a clock face, with no date associated with it ↩

[5] We even say this on the PlainDateTime documentation page ↩

[6] We don’t have methods like isBefore()/isAfter() in Temporal, but this is a place where they’d be useful. These methods seem like good contenders for a follow-up proposal in the future ↩

[7] Intervals bring all sorts of tricky questions too! Some other date-time libraries have interval objects. We also don’t have these in Temporal, but are likewise open to a follow-up proposal in the future ↩